rhyparography

(n.) [rɪpəˈrɑɡrəfi] — the painting of distasteful or sordid subjects. Also: writing about distasteful or sordid subjects (OED)

So what qualifies as “distasteful” or “sordid”? And would photographic images and not just paintings or sketches of subjects which might be characterized by either adjective also be classed as ryparographic? Would photos or videotapes of impoverished, starving Sudanese or of decapitated or dismembered Palestinian babies or toddlers, if beautifully composed and artistically or dramatically lit, be included in this category, compositions distinguished from among the many such photos and descriptions available documenting the full horror of the famine in Sudan and the bombing, shelling and resulting famine in Gaza going on now for the last 8 months? Do Matthew Brady’s photographs of our Civil War dead lying on the ground bloated from decomposition qualify as ryparography?

My suspicion is that such things surpass the “distasteful” and “sordid” characterization which might have made sense to the sensibilities of those living in former centuries and using this word when far less evidence of the grotesque extent of human depravity was within the everyday experience of common humanity. And this obliteration of a clear idea of or a limit on what is considered “distasteful” or “low” explains, perhaps, why this word is not widely known or used today except very occasionally by those whose professional concern is with the criticism of the works of artists and writers thought worthy of critical attention. Even artists as highly esteemed these days as Caravaggio, often when his works were first attracting attention, was disparaged and accused of depicting “sordid” subjects, generally because the models he selected to render these images were thought “low” and unworthy of being the subjects of “high art.” One of Caravaggio’s most admired paintings, for example, The Death of the Virgin, was by some considered offensive and eligible to be labeled “ryparographic” but not because the apparent subject, God forbid, was thought distasteful or sordid—though some did object that to depict the death of Mary was perhaps suspect if not sacrilegious under the belief that as the mother of God she could not have suffered an earthly death but underwent “assumption” directly into eternal “life” [How’s that for a paradox?]—but because the model Caravaggio used in rendering the image of the Virgin Mary was said to be a prostitute.

So maybe it’s not just the subject itself that defines ryparography but also the manner of representation. In this connection one might recall Rudolph Giuliani, as mayor of New York, railing against Chris Ofili’s depiction of the same Virgin in a work he titled

… The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), which plays off classical iconography, depicting Virgin Mary as a black woman made of elephant dung and set against a shimmering gold background replete with women’s buttocks cut from pornographic magazines.1

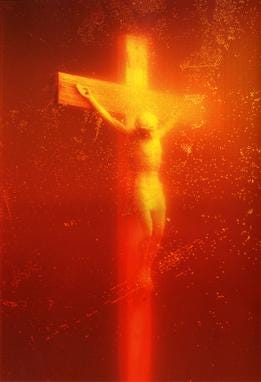

Similarly, many people were offended when a photograph was exhibited, said by the artist, Andres Serrano, to be of a small plastic crucifix immersed in a glass of orangish fluid that the artist claimed was his own urine. Serrano called his work “Immersion (Piss Christ).”2 And yet, sad to say, nowhere in the reporting on either of these two controversies was today’s WOTD used. Go figure.

But maybe “offensive” depiction of religious icons or subjects is something else, something other than ryparography, and this failure to use the word is not just the result of ignorance. If the depiction in whatever medium doesn’t just violate prevailing social norms of what is in “good taste” and “wholesome,” but spills over and violates what believers in some religion or other consider to be the sanctity of their icons or beliefs, does that become a different kettle of fish? Is an image of crucified Christ in a jar of urine just “distasteful” or “sordid” or is it something worse? Is it blasphemous and as such, do we need a new word altogether to name it, since ryparography, this new-old word doesn’t capture this higher level of offense to the public’s sense of decorum? Does ryparography cover these examples as well as Charlie Hebdo and their cartoons depicting Muhammad when Muslims find any depiction of the Prophet unacceptable, let alone depictions that make satiric sport of him?

For contrast and the clarity it can provide, it might add something to this discussion to consider what a late nineteenth century critic, George Saintsbury, had to say about a satirist who in his most significant work satirized a far different subject with a tone and attitude not unlike Alexander Pope had adopted in The Rape of the Lock. The satirist was John Wolcot (aka Peter Pindar) and the work was the Lousiad, the “epic” tale in five Cantos of what occurred when King George III discovered a louse on his dinner plate. Wolcot/Pindar opens Canto I thus,3 in mock-heroic fashion:

THE LOUSE I sing who from some head unknown, Yet born and educated near a throne, Dropp’d down (so will’d the dread decree of Fate!) With legs wide sprawling on the Monarch’s plate: Far from the raptures of a wife’s embrace; Far from the gambols of a tender race, Whose little feet he taught with care to tread Amidst the wide dominions of the head; Led them to daily food with fond delight, And taught the tiny wand’rers where to bite; To hide to run advance or turn their tails, When hostile combs attack’d or vengeful nails: Far from these pleasing scenes ordain’d to roam, Likewise Ulysses from his native home; Yet, like that sage, though forc’d to roam and mourn Like him. Alas! not fated to return! Who full of rags and glory saw his boy*, And wife** again, and dog*** that dy’d for joy. Down dropp’d the luckless LOUSE with fear appall’d, And wept his wife and children as he sprawl’d. *Telemachus **Penelope ***Argus, for whose history see the Odyssey.

Wolcot goes on to describe how the King copes with this insult to his majesty and the dignity of his household by, among other things, insisting that everyone on staff have their heads shaved. Harmless, some would say charming stuff, stuff far from what most today, I feel reasonably certain, would regard as “distasteful” and “sordid”; Saintsbury admits as much and more, even while he avows Wolcot could be classified as a ryparographer in being quick to praise him as a writer of this “lower kind of satire.”

Neither Charles the Second [1630-1685] at the hands of [Andrew] Marvell [1621-1678], nor George the Fourth [1762-1830] at the hands of [George] Moore [1852-1933], received anything like the steady fire of lampoon which [John] Wolcot [1738-1819; aka “Peter Pindar”] for years poured upon the most harmless and respectable of English monarchs. George the Third [1738-1820] had indeed no vices [a claim hard to credit],—unless a certain parsimony may be dignified by that name,—but he had many foibles of the kind that is more useful to the satirist than even vice. Wolcot’s extreme coarseness, his triviality of subject, and a vulgarity of thought which is quite a different thing from either, are undeniable [emphasis added]. But The Lousiad (a perfect triumph of cleverness expended on what the Greeks called rhyparography), the famous pieces on George and the Apple Dumplings and on the King’s visit to Whitbread’s Brewery, with scores of other things of the same kind (the best of all, perhaps, being the record of the Devonshire Progress), exhibit incredible felicity and fertility in the lower kinds of satire [emphasis added]. This satire Wolcot could apply with remarkable width of range. His artistic satires (and it must be admitted that he had not bad taste here) have been noticed. He riddled the new devotion to physical science in the unlucky person of Sir Joseph Banks; the chief of his literary lampoons, a thing which is quite a masterpiece in its way, is his “Bozzy and Piozzi,” wherein [James] Boswell and Mrs. Thrale are made to string in amoebean fashion the most absurd or the most laughable of their respective reminiscences of [Dr. Samuel] Johnson into verses which, for lightness and liveliness of burlesque representation, have hardly a superior.4

Works whose expression is “coarse” and focused on trivial subjects with a “vulgarity of thought” that leaves the reader wallowing in the proverbial gutter—that is what ryparography is, and I along with Mr. Saintsbury like a good burlesque every once in a while too. Expressions which criticize or denigrate or disparage religious beliefs or icons also have their place in a liberal democracy and perforce should be tolerated. Just because you venerate something doesn’t mean anyone else has to do the same nor does it mean that those you may think have insulted any of your cherished beliefs in or about anything whatsoever should be legitimately silenced, beaten or killed. But I don’t think such “insults,” if that’s what they are, qualify as ryparography.

See Why Rudy Giuliani’s Attempt to Close the Brooklyn Museum Is More Relevant Now Than Ever | Artsy if you’ve forgotten or never knew of this episode in Giuliania, an episode of perormative rage that devolved to focus on whether public funds should be used to host the exhibition of such works in public museums.

See Piss Christ - Wikipedia for a bit more about this work and the controversy it inspired.

John Wolcot, The Lousiad (Paris: Parsons and Galignani, n.d.), p. 5. See The Lousiad - Google Books for the entire epic in 5 Cantos.

George Saintsbury, A History of Nineteenth Century Literature (1780-1895) (London and New York: Macmillan and Co. 1896), p. 22.