cacogenics

(adj.) [kakəʊˈdʒɛnɪks] — the breeding of a weak race (OED)

cacogenic

(adj.) [kakəʊˈdʒɛnɪk] — the reverse of eugenic = dysgenic (OED)

See also

dysgenic

(adj.) — exerting a detrimental effect on the race, tending towards racial degeneration, relating to dysgenics — racial degeneration, or its study, as spec. opposed to

eugenic

(adj.) — of or relating to eugenics (n.) — plural form with singular agreement. Eugenics signifies “the study of the arrangement of human reproduction in order to increase the proportion of characteristics regarded as desirable (or to reduce the proportion regarded as undesirable) within a population or the species as a whole. Also: the advocacy for or implementation of policies and practices intended to influence human reproduction in this way.” (OED)

With apologies to those of you who may be familiar with this general history, the idea persists that it may be possible to either “improve” or “disimprove” (on analogy with “disinform” and “disinformation”) the “race” or the species—assuming that is what is meant in this context by “the race”—and it may therefore be worth taking another look at where all this talk, at least in its “scientific” garb, appears to have begun and amounted to before welcoming cacogenics and cacogenic into our vocabularies, if that pair of words isn’t already there.

Of course, folk-wisdom tells us and “everybody knows”—or at least is prone to observe from time to time—”the apple/acorn doesn’t fall far from the tree,” which adage, though the metaphor is misleading, seems intended to mean that the offspring tends to be very like the parent. It’s typically uttered whenever someone’s child does something you think “dumb” or craven or illegal and you already take a dim, unflattering view of his or her mother or father. I would venture that it’s likely this observation’s been made by people all over the world for centuries. But eugenics as a statistical study and a “science” is only about a century and a half old, having been first proposed and “developed largely by Sir Francis Galton [who considered it] … a method of (supposedly) ‘improving’ the human race (OED),” or as Galton himself wrote,

Its [this book’s] intention is to touch on various topics more or less connected with that of the cultivation of race, or, as we might call it, with “eugenic” * questions, and to present the results of several of my own separate investigations.

* That is, with questions bearing on what is termed in Greek, eugenes, namely, good in stock, hereditarily endowed with noble qualities. This, and the allied words, eugeneia, etc., are equally applicable to men, brutes, and plants. We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognisance [sic] of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had. The word eugenics would sufficiently express the idea; it is at least a neater word and a more generalised [sic] one than viriculture, which I once ventured to use.

To which Galton adds, a few pages later,

The investigation of human eugenics—that is, of the conditions under which men of a high type are produced—is at present extremely hampered by the want of full family histories, both medical and general, extending over three or four generations. There is no such difficulty in investigating animal eugenics, because the generations of horses, cattle, dogs, etc., are brief, and the breeder of any such stock lives long enough to acquire a large amount of experience from his own personal observation. … Believing, as I do, that human eugenics will become recognised [sic] before long as a study of the highest practical importance, it seems to me that no time ought to be lost in encouraging and directing a habit of compiling personal and family histories.1

The OED hastens to point out that eugenics “[has been] increasingly discredited as unscientific and racially biased during the 20th cent[ury], especially after its doctrines were adopted by the Nazis in order to justify their treatment of Jews, disabled people, and other minority groups.” Trust the Nazis to shitify everything they touch and, in fairness, just about everything they’ve touched does stink. And yet the idea itself does strike many otherwise intelligent and humane people as something that may have some truth to it, even if it is one of those subjects that is almost always undiscussable for what are obviously historical and political reasons.

Nonetheless, to push ahead, eugenics, dysgenics, and cacogenics could not even have been conceived in their present “modern” form before the development of the idea that species evolve, more or less in accordance with the theory of natural selection, the full formulation of which theory, though refined and altered over the years, has been widely accepted and credited to Charles Darwin (1859), or also before Gregor Mendel’s experiments with hybridization (1865-66) demonstrating that it is possible by “selectively breeding” pea plants to produce offspring having predictable characteristics. From here it is no far stretch to think and to suggest that it may be possible to manipulate genetic combinations by carefully selecting “parents” (in the broad, genetic sense) as well as these days by directly manipulating genes to produce offspring from plants, animals and even humans with certain predictable characteristics that may be considered desirable or to suppress or eliminate certain other characteristics in offspring that may be considered undesirable, and so assume the role of evolution’s little assistants.

But if you think about it, cacogenics and eugenics, while not seeming at all irrational, “crazy” ideas, are essentially without content—except perhaps at the level of the simpler organisms or organisms bred primarily for specific, commercially useful characteristics—because there is just too much that is unknown about genes and their effects and the effects of their combinations, and too much that is unknown about the connections between an organism’s genetic constitution and the physical and behavioral characteristics of those same organisms, and too much that is unknown—and maybe unknowable—about the effects of environmental factors on genetic constitution to be able to confidently predict much about how the kids are going to turn out.

And yet these ideas don’t go away; they constitute an important element of our culture’s matrix, so to speak, and—apart from considerations of the sleazy influence of money—they legitimate and underlie everything from a belief in the virtues of aristocracy and “legacy university admissions” to the belief that some people come from the “right families” and some don’t, beliefs that are often the themes of novels (e.g., The Bad Seed) and satires (e.g., Caddy Shack). And in spite of it all, we do have thoroughbred race horses running at Churchill Downs and intergenerational all-star baseball players like Ken Griffey (father) and Ken Griffey, Jr. (son), and basketball families like Adrian Griffin and his children Adrian Griffin, Jr., Alan Griffin and Aubrey Griffin, whose shared exceptional athletic performance can hardly be simply the result of hard work and dedication, and let’s not forget that GMO vegetables and, for all anyone really knows, steak and hamburger meat are for sale at the local supermarket.

It should also not be forgotten that many well-regarded writers have well understood and even subscribed to and advocated these ideas. George Bernard Shaw, for example, wrote that under capitalism

… most of those ministering to your wants are not in personal contact with you. They are the employees of your tradesmen; and as your tradesmen trade capitalistically, you have inequality of income, unemployment, sweating, division of society into classes, with the resultant dysgenic restrictions on marriage., and all the other evils which prevent a capitalist society from achieving peace or permanence.2

I think when he says “dysgenic restrictions on marriage,” Shaw means restrictions on most procreation, such as laws against interracial marriage or other such prohibitions on marrying out of your class or religious or ethnic group that the imposers of those prohibitions believe produce offspring that debase the race whatever they may imagine such debasement to consist of.

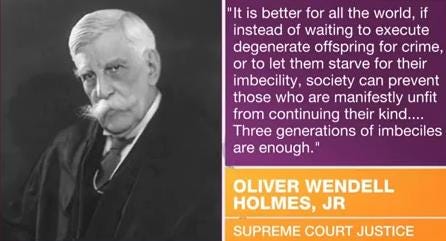

* Buck v. Bell :: 274 U.S. 200 (1927) :: Justia US Supreme Court Center

About 300 pages later, Shaw returns to the topic in discussing the diminished power of religion as providing a reliable guide to what might be done to improve the conditions of life:

… we have arrived at a point at which, from one end of our lives to the other, we are not compelled by law to pay a penny to the priest unless we are country landlords, nor attend a religious service, nor concern ourselves in any way with religion in the popular sense of the word. Compulsion by public opinion, or by our employers or landlords, is, as we have seen, another matter; but here we are dealing only with State compulsion. Delivered from all this, we are left face to face with a body of beliefs calling itself Science, now more Catholic than any of the avowed Churches ever succeeded in being (for it has gone right round the world), demanding, and in some countries obtaining, compulsory inoculation for children and soldiers and immigrants, compulsory castration for dysgenic adults, compulsory segregation and tutelage for “mental defectives”, compulsory sanitation for our houses, and hygienic spacing and placing for our cities, with other compulsions of which the older Churches never dreamt, at the behest of doctors and “men of science”.3

Shaw’s use of dysgenic here is evidence not only that he understood the concept but that he saw it as a live concern of people who were now believers in science instead of religion as the way to truth and sensible social policy, people, moreover, who were eager to impose their new scientific beliefs on the rest of us—how contemporary can you get! His tone, however. suggests that he took a skeptical view of the belief that their claims to enhanced understanding based on “science” would lead to what they believed it would, that is, both to enhanced social policy and the improvement of the race, or at least provide to a check on its deterioration.

Another writer, William Ralph Inge, one whose name was apparently proposed thrice for the Nobel Prize in literature,4 enthusiastically welcomed science as the road to both the improvement of the conditions of human life and to the improvement of the species, and him being a white Englishman educated for the ministry at Oxford and, in a real sense, “to the manor (manner) born,” we can imagine rather clearly what he probably thought would be the likely incarnation of such an improvement. To this end, he seems to have believed eugenics might be the appropriate means, though he recognized that the “science” that might support eugenics was yet a long way from providing definitive guidance about how to proceed. We have, he noted,

… our duty to posterity. Here again, new scientific discoveries have called attention to the fact that we are largely responsible for the physical, intellectual, and moral outfit with which the next generation of English will face the duties and difficulties of life. The science of eugenics is still in its infancy, and the wisest students of it warn us not to be in a hurry; but no one can read the standard books on Mendelism without being convinced that an instrument has been put into our hands by which real racial progress can be attained in the future. It is equally certain that in the absence of purposive action directed towards racial improvement, civilisation [sic] itself will prove a potent dysgenic agency, sterilising [sic] the best stocks and encouraging the multiplication of the unfit. To any intelligent lover of his kind, this must seem the most important of all social questions, and the encouragement of scientific research in this direction must seem the most hopeful means of helping forward the progress of humanity.5

Of course, if he believed the race can be improved, it could conversely become debased and subject to dysgenesis and cacogenesis. Indeed, Inge seemed more concerned with arresting the deterioration of the human race than in promoting its improvement. After putting in a good word for what he believed were the eugenic effects of a prudent imperialism, Inge observes that

The notion that frequent war is a healthy tonic for a nation is scarcely tenable. Its dysgenic effect, by eliminating the strongest and healthiest of the population, while leaving the weaklings at home to be the fathers of the next generation, is no new discovery. It has been supported by a succession of men, such as Tenon, Dufau, Foissac, de Lapouge, and Richet in France; Tiedemann and Seeck in Germany; Guerrini in Italy; Kellogg and Starr Jordan in America.6

A couple of years later he went on to amplify his warning about this generally unremarked effect of war:

The most expeditious mode of strangulation is probably war, a ruinously dysgenic institution, which carefully selects the fittest members of the community, rejecting the inferior specimens, takes them away from their wives for some of the best years of their lives, and kills off one in ten or one in five, as the case may be. The loss inflicted on our race by the Great War can never be repaired; the average quality of the parents of the next generation has been greatly lowered, and this evil is irremediable.7

And he added his concern about what he believed were the dysgenic effects of the overthrow of existing social and economic class structures:

Hardly less destructive is social revolution, as we have seen it at work in Russia. The trustees of such culture as existed in Russia have been exterminated; civilization in that unhappy country has been simply wiped out in a few years, and the nation has reverted to absolute barbarism.8

And to cap off his concerns for the state and future of the race, he weighs in on what he sees as the destructive effects of Catholicism and of Christian religions more generally:

The kindred problem of regulating the population so as to secure the best conditions for the inhabitants of a country must also, before long, engage the attention of all intelligent sociologists. But here, also, the old morality is the great enemy of the new. The Roman Catholic Church is a bitter and unscrupulous opponent both of eugenics and of birth-control. I read in one of their organs the astounding statement that ‘since posterity does not exist, we can, properly speaking, have no duties towards it.’ Only those who have tried to rouse public conscience on these questions know how fierce is the antagonism of the greatest among Christian Churches to any recognition of scientific ethics.9

So what’s the upshot? We still have the Darwin Awards10 to keep us all amused, but what else is in store for us all on the eugenic, dysgenic and cacogenic front in the decades ahead I’m sure will not be as amusing, especially for those who believe that cloning and genetic modification, in short, human hubristic messing with Mother Nature pave the road to perdition as well as to biologic catastrophe. Fortunately, most of us won’t be around to see or worry about whether or not the Proud Boys have indeed seen to it that their white, European genetic purity has been preserved, though I really doubt they will have done so, and I for one think their failure will be a good thing too.

In the meantime, I give you another couple of words to use in your conversations and deliberations about these matters if you’re interested. But before putting a period to this brief disquisition, I would like to sound a note of caution: let us all be very careful how we understand and use this set of WsOTD, as hasty, simple-minded understanding and applications of these concepts can certainly be socially destructive, and we surely don’t need any more of that.

Francis Galton, Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development (London and New York: Macmillan, 1883), pp. 24-25; 44-45. See Inquiries into human faculty and its development : Galton, Francis, Sir, 1822-1911 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive for the full text of Galton’s book.

To a different purpose, one might wonder if the recent rise in the interest in finding one’s “roots” and the popularity of outfits like Ancestry.com and “23 and Me” which purport to help you locate not only your relatives but also where your ancestors came from by examining archival records as well as your DNA is motivated by just this need, long somewhat dormant in the general population, to find out just who and what we are.

George Bernard Shaw, Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (New York: Brentano’s Publishers, 1928), Section xxxviii., p. 149-150. See The intelligent woman's guide to socialism and capitalism : Shaw, Bernard, 1856-1950, author : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Ibid., pp. 436-437.

William Ralph Inge, Outspoken Essays: Second Series (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971 (1922), p. 57. See Outspoken essays (second series) : Inge, William Ralph, 1860-1954 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive for the entire Second Series volume.

William Ralph Inge, Outspoken Essays: First Series (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971 (1919), p. 41. See Outspoken essays (first series) : Inge, William Ralph, 1860-1954 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive for the entire First Series volume.

Inge, Outspoken Essays: Second Series, pp. 264-265.

Ibid., p. 265.

Ibid., pp. 57-58.